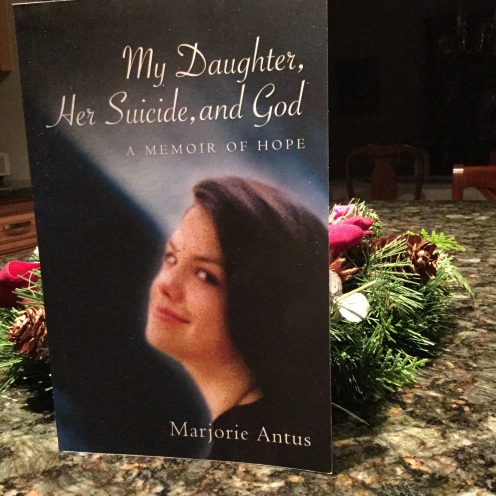

My brother George sent this picture a couple of weeks ago. He’s holding my daughter Mary at a Virginia horse farm on an autumn Sunday in 1980. She was three years old at the time, a delightful child, full of wonder, who would die by intentional overdose fifteen years later.

During the first dozen years of my grief for her, seeing the photograph would have jarred a routine question: “How on earth did my adorable little girl ever get to a place in her life where she felt she had to die?”

It was a question without answer, an insistent probe into the reality of my daughter’s life. In early grief, that sweet, innocent picture of Mary would not have seemed sweet and innocent. It would have called into doubt every good quality she possessed throughout her life. It would have prompted me to read the ugliness of her suicide back into the beauty of that picture-perfect moment. It would have left me grappling with the fear that, at depth, life makes no sense.

An essential part of healing after suicide is that of reviewing one’s relationship with the deceased and exploring how it can be “disentangled from the manner of death . . .” clinical researchers John Jordan and John McIntosh advise (Grief After Suicide: Understanding the Consequences and Caring for the Survivors, New York: Routledge, 2011, 200).

Disentangling Mary from her suicide required the discipline of many years: clearly the most arduous inner housecleaning of my life. But it finally gave my daughter back to me in a healing, peaceful way. Even more, it allowed the beauty of her life to return in its fullness.

Seeing the picture of her and my brother now brings profound gratitude. It calls up several lines from John Keats’s poem Endymion that I have been waiting to use ever since I memorized them in college forty years ago: “A thing of beauty is a joy for ever: / its loveliness increases; it will never / Pass into nothingness.”